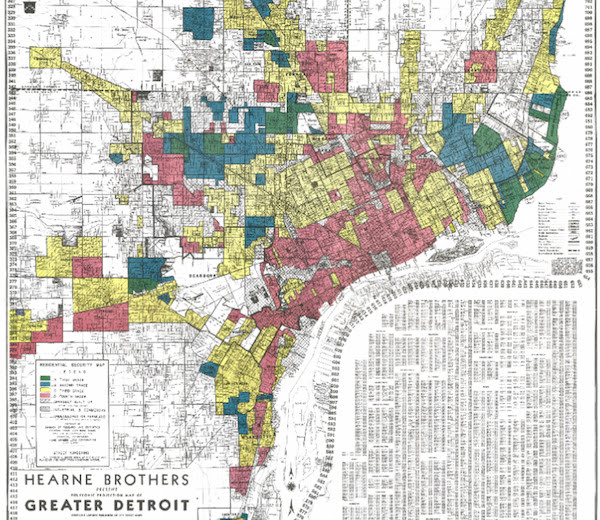

Back in 1968, redlining — or refusing to give loans to residents of certain neighborhoods, and a tool of discrimination against blacks — was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act. It was a landmark victory for the Civil Rights movement, but it’s not exactly ancient history. You still find the language from racially restrictive covenants (banned even earlier) in the deeds to homes. And, among the many harmful outcomes of segregation, it’s worth considering how historic redlining affects residents of those neighborhoods today, researchers suggest in a recent study.

“The legacy of redlining in the effect of foreclosures on Detroit residents’ self-rated health,†published by University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill researchers in the peer-reviewed journal Health & Place, looks at the impact of the Great Recession and foreclosures on Detroiters’ heath. They analyze how mortgage foreclosure rates changed by neighborhood after 2008 and surveys of how residents rated their own health, from excellent to poor. What they found wasn’t exactly simple, and they noted a bunch of other factors (like urban renewal and other kinds of housing discrimination) that weren’t factored in to the data.

But the TL;DR is: in neighborhoods that were slower to recover from the Great Recession, residents were more likely to rate their own health as poor.

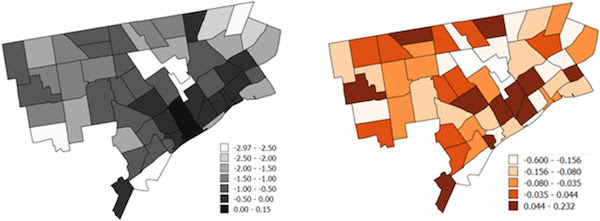

Right: Change in Prevalence of Poor Self-rated Health 2008–2012. Areas with darker shading experienced increases in the prevalence of poor health, while lighter shading indicates decreases. Via Science Direct

Other scholars have also found links between health problems and areas with high foreclosure rates after the financial crisis. This recent study, however, takes a more historical look, and overlaid redlining maps onto their foreclosure data. What they determined: “Redlining history was strongly associated with post-Recession foreclosure rate recovery and self-rated health.”

The authors warn not to take the research as a prescriptive or to view it in a vacuum. But they suggest that it’s important for advocates and policymakers to take this type of history into account for more effective neighborhood health interventions — addressing foreclosure’s effects alone won’t solve the larger problems. They use the example of the city’s demolition program, which is dealing with the aftermath of foreclosures by clearing thousands of houses, but doesn’t address health disparities (and in fact has some people concerned that it could cause health problems.)

Here’s their examples of a more holistic approach, taking historical discriminatory practices into account: “community-driven identification of the lenders most likely to foreclose on individual home owners over the last two decades in Detroit,†and “litigation to reclaim property and secure reparations related to unjust foreclosures. … Such interventions demonstrate understanding of the historical determinants of racial and socioeconomic differences in foreclosures, and begin to address the combined impacts of discriminatory practices and policies.â€

Get into the nitty gritty with the full article here. And then, revisit Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article “The Case for Reparations†for a much more in-depth look at the contemporary consequences of redlining and other housing discrimination.

NO COMMENT